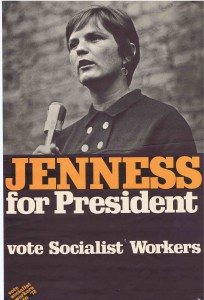

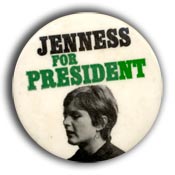

Calling President Richard M. Nixon “an international outlaw” on this day in 1972, the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) candidate for president of the United States urged students  at the University of Arizona in Tucson to join the antiwar movement.

at the University of Arizona in Tucson to join the antiwar movement.

at the University of Arizona in Tucson to join the antiwar movement.

at the University of Arizona in Tucson to join the antiwar movement.As part of a two-day swing through the Grand Canyon State that also included an appearance at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, Linda Jenness told the students that “if you have any ounce of decency left in you, you’ll join the antiwar movement and organize and support activities in this city.”

Jenness, who was radicalized by the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War, didn’t mince words.

“The Vietnamese are not international outlaws as the President called them,” continued the little-known minor-party candidate. “They are not bombing our cities or turning our crops and forests into wasteland.”

“Why don’t Americans have prisoners of war,” she asked the more than 250 students in attendance at Northern Arizona the next day. There’s a simple reason, she explained, answering her own question. That’s because all of the prisoners taken by the United States “are shot,” not captured.

While that wasn’t quite true — between 1966 and 1968 the U.S. built at least six POW camps in Bien Hoa, Pleiku, Can Tho, Qui Nhon, Phu Quoc Island in the Gulf of Thailand, where an estimated seven in every ten prisoners were interned, and Da Nang, South Vietnam’s second largest city, altogether holding approximately 20,000-30,000 North Vietnamese POW’s — the Trotskyist candidate, echoing what was universally believed on the far left at the time, nevertheless made her point about alleged American brutality and ruthlessness and gained a few young converts in the process.

The widely-publicized My Lai Massacre, in which between 350 and 500 unarmed civilians, including countless women, children and elderly, were mercilessly slaughtered at the hands of Lt. William Calley and other U.S. servicemen in March 1968, made almost anything believable during that unjust and unimaginably bloody conflict. It was one of the most tragic and shameful episodes in American history.

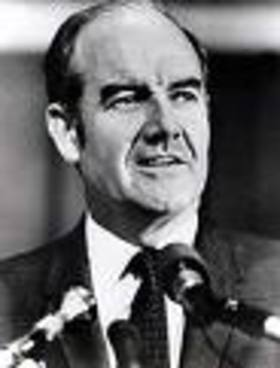

Earlier that month, Jenness, who had waged unsuccessful write-in campaigns as her party’s candidate for mayor of Atlanta in 1969 and for governor of Georgia in 1970 — garnering more than 500 votes from those who had scribbled in her name in the latter contest — had challenged Sen. George S. McGovern to a debate while both of them were appearing at campaign events at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

It was the second time since October that she had asked McGovern, who was still a dark-horse candidate for the Democratic nomination, to share a podium with her.

McGovern refused both times.

Refusing to wilt away as a dying flower or some sort of minor nuisance, the pesky Socialist Workers’ candidate stepped up her attacks on the Democratic peace candidate, faulting the South Dakota lawmaker for voting for the Gulf of Tonkin resolution in the Senate in 1964, and for voting against its repeal in 1967. She also said that McGovern — the eventual Democratic nominee — had supported several appropriations bills funding the war in Southeast Asia.

“The very least an anti-war senator could do is vote against war appropriations,” she sighed.

Earlier in the year, the militant third-party candidate had succeeded in convincing Rep. Paul McCloskey, an antiwar congressman from California who was challenging Nixon for the 1972 Republican presidential nomination, to debate her during the New Hampshire primary. Hoping to replicate Eugene McCarthy’s stunning feat against LBJ in New Hampshire four years earlier, the liberal congressman from California had spent nearly a million dollars in trying to upset Nixon in the Granite State’s first-in-the-nation primary.

McCloskey’s acceptance was quite a coup for the relatively obscure socialist candidate for the White House, who argued in their January 15 debate at Colby College that voting against Nixon in the Republican primary wasn’t the way to bring about real change.

“Change,” she asserted, “comes through massive protest in the streets.”

Jenness, a graduate of Antioch College, had no such luck with her potential Democratic sparring partner.

McGovern’s refusal to debate sparked a lively exchange between the two, one that was amply covered in the pages of The Militant, the party’s official newspaper, which was then edited by Jenness’s husband. Though largely forgotten today, it was arguably the most interesting give-and-take between a major party candidate and a so-called “fringe” challenger in American history.

In his January 14 reply to the Socialist Workers candidate, McGovern said that he felt as though he was being unfairly “singled out as a special target” by the SWP and defended his support for military funding because he didn’t want “to see American troops abandoned in Vietnam.” He also said that he had voted to repeal the Gulf of Tonkin resolution in 1970, the first time it came up for a vote in the U.S. Senate.

In his January 14 reply to the Socialist Workers candidate, McGovern said that he felt as though he was being unfairly “singled out as a special target” by the SWP and defended his support for military funding because he didn’t want “to see American troops abandoned in Vietnam.” He also said that he had voted to repeal the Gulf of Tonkin resolution in 1970, the first time it came up for a vote in the U.S. Senate.The plain-spoken Jenness responded ten days later, reminding the South Dakotan that he had voted to table an amendment to repeal the Tonkin resolution on March 1, 1966. She also took him to task for voting in favor of defense appropriations and military funding because, as he admitted in his letter, he firmly believed the the United States needed an adequate national defense.

“If you were elected,” Jenness replied, “your foreign policy would not differ fundamentally from that of your predecessors — Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon — in that its foundation would be the maintenance of American imperialism.”

In the course of their back-and-forth exchange, Jenness opined in an interview that the Democratic primaries were of little value for anybody seeking real change. “The primaries are an effort to make the system seem democratic,” she scoffed. “But 1968 should have taught people that the choice of the rank and file [Eugene McCarthy] doesn’t get the nomination.” She was right; Humphrey, the unimaginative administration loyalist who didn’t win a single primary in 1968 when McCarthy risked his political career and Bobby Kennedy belatedly sacrificed his life in pursuit of their party’s nomination, was nominated overwhelmingly in Chicago.

In many ways, Jenness, the daughter of an Oklahoma veterinarian — a man she shruggingly described as “a reactionary,” a possible George Wallace supporter — was a wildflower in American politics, a woman who “refused to wither in place, a rambling rose seeking mysteries untold, no regrets for the path that she chose,” as our country’s most profound and authentic lyricist once described the uncultivated plants growing unattended in fields and forests across this great country.

It’s true that she was a radical Trotskyist, but she also spoke truth to power, long before that was fashionable.

A 31-year-old secretary from Atlanta, Jenness had been nominated for the nation’s highest office at the Socialist Workers Party’s national convention in Cleveland, Ohio, the previous August, along with her vice-presidential running mate — 21-year-old Andrew Pulley of Chicago, an African-American activist and co-founder of GIs United Against the War who had been placed in a military stockade at Fort Jackson because of his antiwar activities. Neither of them met the constitutional requirement that the president and vice-president must be at least 35 years of age. It was a requirement that didn’t faze Jenness in the least.

“We think that constitutional requirement is ridiculous,” Jenness told the Capital Times in Madison, Wisconsin. “Turning 35 does not make you a genius, politically, as so many of our politicians have proven,” she said. “McGovern should join us in efforts to change that requirement.”

“Let me assure you,” she said shortly after winning her party’s nomination, “if a majority of the people elect me as president, they will see I am put in office.”

The SWP had high hopes entering the 1972 presidential campaign, promising, in the words of party leaders, “the largest campaign we’ve ever run” — the most concerted socialist campaign since 1920 when Eugene V. Debs, imprisoned for giving an antiwar speech during World War I, received nearly a million votes from a prison cell. The party hoped to raise close to $500,000 and place its presidential ticket on the ballot in at least thirty to thirty-five states that fall — a significant increase over the $40,000 spent on behalf of antiwar activist Fred Halstead’s candidacy in 1968.

raise close to $500,000 and place its presidential ticket on the ballot in at least thirty to thirty-five states that fall — a significant increase over the $40,000 spent on behalf of antiwar activist Fred Halstead’s candidacy in 1968.

raise close to $500,000 and place its presidential ticket on the ballot in at least thirty to thirty-five states that fall — a significant increase over the $40,000 spent on behalf of antiwar activist Fred Halstead’s candidacy in 1968.

raise close to $500,000 and place its presidential ticket on the ballot in at least thirty to thirty-five states that fall — a significant increase over the $40,000 spent on behalf of antiwar activist Fred Halstead’s candidacy in 1968.“We’re going to speak to tens of millions of people,” declared Jenness, “and explain to them the rottenness and corruptness of the Democratic and Republican parties.”

With the Watergate scandal unfolding in the background only a few months later, there wasn’t a whole lot of explaining for Jenness to do. Corruption was endemic in American politics. Jenness, of course, didn’t expect an illegal contribution of $400,000 from ITT, similar to the giant International Telephone and Telegraph conglomerate’s secret donation to Nixon’s Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP) in the spring of 1971 to help finance the GOP’s national convention in San Diego in exchange for dropping the Justice Department’s antitrust suit against the corporation.

Fearing a major scandal — thanks largely to the intrepid Jack Anderson — the Republican convention (it was really just a symbolically meaningless coronation of a crook) was eventually moved to Miami Beach.

The system itself was poisoned — and the American people, at least those who were paying attention, knew it.

Though she was right about corruption and the war, Jenness knew from the outset that victory for her tiny left-wing party wasn’t possible — at least not in 1972. “The Socialists do not fool themselves that they have a chance of winning any major victories this year,” she said in an interview with the New York Times in June. “But I do believe I will live long enough to see a Socialist government in this country.”

“The problems the American people are facing are increasing,” she said in an interview earlier in the campaign. “So people start becoming radicalized.”

Yet, there was hope — plenty of hope. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” said one longtime left-winger in Massachusetts after the party collected 100,000 signatures in a three-week period to qualify for the ballot in the Bay State. It was an amazing accomplishment, a real grassroots display of democracy — the kind of genuine volunteer effort glaringly absent from American politics in the Internet age.

In many respects, the liberal bastion of Massachusetts marked the apex of the SWP’s 1972 campaign and it showed in the election results when Donald Gurewitz of Boston, a 25-year-old activist in the Young Socialist Alliance — the party’s youth organization — garnered 41,369 votes for the U.S. Senate.

The low-key Jenness, who usually wore little or no makeup and almost always dressed in a plain pantsuit — coming across rather conservatively to friend and foe alike on the campaign trail — was a pragmatist. She had street smarts when it came to politics.

“We don’t have any illusions about changing this country through the electoral system,” she said in another interview. “This campaign is just an opportunity for us to gain some new members, to challenge some restrictive election laws and generally to alert people to the undemocratic nature of the whole capitalistic system,” she said.

Though falling far short of her party’s stated goals — raising slightly less than a quarter of the $500,000 budgeted for the campaign while appearing on the ballot in just 25 states — a modest increase of six states over 1968 when Fred Halstead polled 41,000 hard-earned votes on the party’s ticket against Dick Nixon, Vice President Hubert Humphrey and Alabama’s George C. Wallace — Jenness campaigned vigorously, appearing frequently at high schools, prisons and antiwar demonstrations across the country. The low-profile candidate was a big hit among the incarcerated.

The cash-strapped candidate, who spoke Spanish more or less fluently, also took time from her busy day-to-day campaign itinerary to conduct a brief, no-frills speaking tour of Mexico, Peru and Argentina later that spring. The coverage of her candidacy in those countries was better than anything she received in the somnolent and jaded U.S. media.

Believing that she might have polled a quarter of a million votes or more if somebody other than McGovern had been the Democratic nominee — polling numbers similar to Debs or the 884,000 votes garnered by the Socialist Party’s Norman Thomas, Debs’ successor and an “ideological Uncle Tom” to the SWP, at the height of the Great Depression was simply out of the question — the woman who proudly preferred the role of revolutionary agitator to that of President nevertheless garnered more than 66,000 votes nationally.

In and of itself, that wasn’t too shabby considering that two of the leading antiwar figures in the country, George McGovern and People’s Party candidate Benjamin Spock, the famous pediatrician and arguably the coolest guy who ever sought the presidency, albeit reluctantly, were also running for president that year.

While fearlessly speaking for America’s better self, the hard-working and unassuming Jenness — the low-profile peace candidate of the historically powerless and voiceless working-class who refused to be stymied by an inattentive media and who valiantly out-hustled her major-party opponents almost every step of the way on what amounted to a shoestring budget — did her tiny party proud.

Pingback: Hillary Clinton and Five Other Women Who Ran For President

Pingback: 5 Other Women Who Ran For President | USA Press

Pingback: SparkLife » The awesome women that paved the way for Hillary Clinton to run for President

Pingback: SparkLife » Hillary Clinton Gets Nomination, Following Long Line of Boss Ladies Who Could Never Be Satisfied