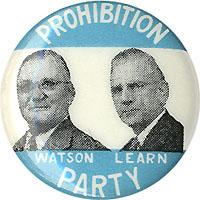

Claude A. Watson, the Prohibition Party’s candidate for president, was unable to vote for himself on this day in 1948.

Claude A. Watson, the Prohibition Party’s candidate for president, was unable to vote for himself on this day in 1948.

Watson and his wife had requested that absentee ballots be mailed to them in Winona Lake, Indiana, where they were attending a church convention, but had decided to return to their home in Highland Park, a suburb of Los Angeles, sooner than expected. It wasn’t until they landed in Los Angeles that Mrs. Watson discovered that she had inadvertently placed their absentee ballots in a suitcase that was being returned to the couple’s home by automobile.

An ordained Free Methodist minister and longtime lawyer who once played minor-league baseball, Dr. Watson — not to be confused with the companion and chronicler in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s famous Sherlock Holmes novels — was determined to cast his vote in the presidential election.

“I’m going down to my precinct and swear out an affidavit that I haven’t voted today,” he told reporters after arriving back in Los Angeles. “Under the election laws, they must then permit us to vote.”

Unfortunately, local election officials disagreed, telling the dry standard-bearer that he and his wife wouldn’t be allowed to vote without first surrendering their absentee ballots — an impossibility considering the car carrying their absentee ballots wasn’t expected to arrive in Los Angeles for a few more days.

The dignified Prohibitionist quietly acquiesced rather than cause a scene in front of his neighbors at his local polling station.

Competing against a field of much better-known rivals, including former Vice President Henry A. Wallace, nominee of the left-wing Progressive Party, and marble-mouthed Dixiecrat J. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, the little-known Watson’s colorful style of campaigning drew considerable media attention that autumn.

Furious that Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson had refused to grant him a permit for air travel during the 1944 presidential campaign — a privilege reserved exclusively for the two major-party candidates that fall — Watson obtained his pilot’s license and purchased a new airplane shortly before the 1948 campaign began.

Crisscrossing the country in his single-engine Stinson Voyager, the ubiquitous Watson made up for his virtual anonymity by seemingly appearing everywhere, logging more than 100,000 miles by air during the ’48 campaign.

Small towns and big cities throughout the country received a visit from the pink-cheeked presidential hopeful who wanted to reduce teen pregnancy and passionately believed that national prohibition had failed only because of the “disgraceful and scandalous failure of enforcement.”

Unlike his party’s previous nominees for the Oval Office, the biographically-neglected Watson — a man who liked to defy the odds and once surprised everybody by garnering a remarkable 332,173 votes in a hopelessly long-shot bid for Los Angeles district attorney — knew how to get attention.

In one widely-reported publicity stunt, he even managed to send his wife, Maude, on a tour of the White House to prepare a list of alterations she would make when he became president. “We’ve already planned for a redecorating scheme when the Democrats move out,” he told reporters in late July.

Claude and Maude couldn’t wait to take up residence in the grand, but neglected mansion.

Though prevented from voting for himself, Watson garnered a relatively impressive 103,489 votes in 33 states that year — the party’s strongest showing in a presidential election since 1920, shortly after the enactment of national prohibition — while finishing sixth nationally, barely 36,000 votes behind the Socialist Party’s widely-recognized Norman M. Thomas who was waging his sixth and final bid for the presidency.

It was the last time a Prohibition candidate for the presidency surpassed the 100,000-vote threshold.

It was also a noticeable improvement over the nearly 75,000 votes cast for Watson as the party’s nominee in 1944 — a year when he and the Socialist Party’s Thomas easily fended off little-known Pennsylvania steelworker Edward A. Teichert, the Socialist Labor Party’s nominee, in their battle for third-place bragging rights.

Watson, then nearly an octogenarian, briefly sought the Prohibition Party’s presidential nomination again in 1964.

ALSO: Bernie at bat? Sanders makes pitch for minor-league baseball

Follow Us