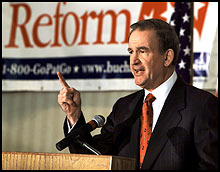

Patrick J. Buchanan, the pugnacious conservative commentator whose insurgent candidacies briefly threatened the GOP’s frontrunners in 1992 and 1996, dropped out of the race for the Republican presidential nomination and announced that he was seeking the Reform Party’s nomination on the last Monday of October in 1999.

Patrick J. Buchanan, the pugnacious conservative commentator whose insurgent candidacies briefly threatened the GOP’s frontrunners in 1992 and 1996, dropped out of the race for the Republican presidential nomination and announced that he was seeking the Reform Party’s nomination on the last Monday of October in 1999.

Promising to shake up American politics, the 60-year-old Buchanan told a packed room of supporters and reporters at the Doubletree Hotel in Falls Church, Virginia, that his decision to leave the Republican Party — a party in which he proudly labored for nearly forty years — was a difficult one.

“This decision was not made without anguish and regret,” he said.

Fondly recalling his years in the GOP — from being perhaps the only Goldwater supporter in the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University in the early sixties to his nine years of service as a youthful speechwriter for Richard M. Nixon and culminating with the heady experience of being at Ronald Reagan’s side when the President walked out of the summit at Reykjavik in the autumn of 1986 after refusing to abandon his missile defense program — Buchanan said the Republican Party had been good to him.

Quoting John F. Kennedy, the lifelong Republican lamented that party loyalty occasionally asks too much. “And today it asks too much of us,” he said.

His words arguably ring even truer today than they did then.

In declaring his party switch, Buchanan said that the two-party establishment had become “a snare and a delusion, a fraud upon the nation.” Neither party, he noted, was speaking for the “forgotten Americans” whose jobs were sent overseas to finance the boom market of the 1990s.

Due to NAFTA and GATT — both of which had been vigorously opposed by Reform Party founder Ross Perot — Buchanan said that America’s industrial base has been hollowed out and that blue-collar workers had been forced to compete with sweatshop labor abroad while the nation had been “left dependent on imports for the vital necessities of national life.”

Buchanan, who had met privately with Reform Party national chairman Russ Verney a few weeks earlier, was just warming up.

“Our two parties have become nothing but two wings of the same bird of prey,” he declared. “On foreign and trade policy, open borders and centralized power, our Beltway parties have become identical twins. Both supported NAFTA and GATT and the surrender of our national sovereignty to the WTO. Both supported the extension of nuclear war guarantees to the borders of Russia. Both supported the illegal war on Serbia. Both support IMF bailouts of corrupt regimes. Both vote for MFN trade privileges for a Communist Chinese regime that today targets missiles on American cities. The appeasement of Beijing is a bipartisan disgrace, and we will not be a part of it.”

He also struck an uncharacteristically conciliatory tone in his long-rumored announcement, speaking passionately of the need for racial reconciliation and assimilation for the nation’s nearly thirty million immigrants who had arrived over the previous three decades.

nation’s nearly thirty million immigrants who had arrived over the previous three decades.

“This land is our land,” said the new warm and fuzzy Pat. “It belongs to all of us, immigrant and native-born alike; and it would be unpardonable ingratitude if we, the children of pioneers and patriots of every color, continent, and creed, lost this last best hope of earth, because we could not learn to live with one another, and could not learn to love one another.”

With a melodramatic flourish, Buchanan asserted that he and his supporters — the fabled Pitchfork Brigade — were refusing to go quietly into the night and that his third-party candidacy was “our last chance to save our Republic, before she disappears into the godless New World Order that our elites are constructing in a betrayal of everything for which our Founding Fathers lived, fought, and died.”

He also had a message for the hucksters on Wall Street and their obedient servants in Washington who thought, at long last, that they had pulled up their drawbridge and locked middle-income and working-class Americans out forever.

“You don’t know this peasant army,” thundered Buchanan. “We have not yet begun to fight.”

For a brief moment, it looked like Buchanan might be right. A Newsweek poll taken only a few days after his announcement showed Buchanan, as a potential Reform Party candidate, polling a solid 7 or 8 percent of the vote in hypothetical three-way contests in the general election.

Buchanan’s announcement that he would seek the Reform Party’s nomination — and its glittering prize of $12.6 million in federal funding — drew mixed reaction within the Republican and Reform Party ranks.

Relieved of the burden of dealing with the populist provocateur in their midst, many Republicans were pleased by Buchanan’s decision. The gay Log Cabin Republicans, whose leader had long considered the conservative firebrand a “cancer” in the party, celebrated his departure.

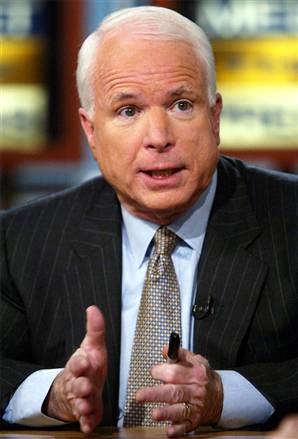

Joining a growing chorus of critics, Sen. John McCain of Arizona was also happy to see him go. Denouncing the country’s increasingly corrupt political system as “a spectacle of selfish ambition” in officially launching his own insurgent candidacy for the party’s nomination only a month earlier, the Arizona lawmaker had been one of Buchanan’s harshest critics.

McCain, who had accused the pundit-turned-politician of straying so far from the American mainstream in his views on foreign policy, particularly his controversial criticism of the U.S. role in defeating Hitler and the Nazis in WWII, had strongly recommended that the party should show him the door — and the sooner, the better.

“I have made no attempts to convince him to stay in the Republican Party and I do not mourn his departure,” said the straight-talking Arizonan.

Unlike McCain, Texas Gov. George W. Bush, whose father had been savaged by Buchanan in the 1992 primaries — Pitchfork Pat delighted in referring to the elder Bush as “King George” — was clearly irritated, saying that Buchanan was leaving the party because the Republican rank-and-file had overwhelmingly rejected his views in three attempts for the party’s nomination.

The establishment’s choice who was then riding a wave of “inevitability,” Bush had personally conducted a months-long charm offensive in a failed attempt to keep Buchanan from bolting. The Texas governor later said that he was confident that the vast majority of the party’s conservatives would refuse to follow Buchanan’s lead, saying there would be no mass exodus from the party.

Political consultant Lyn Nofziger, a one-time Buchanan supporter, concurred. “I think they will stay in the party,” reasoned Nofziger, “because people don’t like to throw a vote away.”

In the meantime, Buchanan’s declaration set off a firestorm of sorts within the Reform Party. While economist Pat Choate, the thoughtful policy analyst who served as Perot’s vice-presidential running mate in 1996, and self-described leftist Lenora Fulani of New York, the longtime African-American activist who had twice sought the presidency as the nominee of the short-lived New Alliance Party, welcomed him into the party with open arms, many of those loyal to Perot were less than thrilled at the prospect of a right-wing takeover of their avowedly-centrist party.

“If Pat Buchanan brings enough people, we become the Pat Buchanan Party and there’s nothing we can do about it,” said a member of the party’s national rules committee. “They can put all our issues on the back burner.”

It was a view echoed by many of the party’s founding members who feared their rag-tag army would be no match for Buchanan’s better-organized forces. “They’ve been around politics a long time, and we’re mostly novices,” sighed the party’s state chairman in Maine.

Some were admittedly torn about a Buchanan candidacy, viewing it as both a blessing and a curse.

“There’s no doubt that this is going to bring more attention and energy to our presidential contest than I could dream of, especially if it gets into an honest contest between two players,” said Minnesota’s Dean Barkley. However, if the conservative pundit didn’t quickly tone down his harsh rhetoric on social issues, cautioned Barkley, “it becomes very problematic.”

Many party members were hoping that a strong challenger to the despised and reviled Republican interloper would emerge before the party settled on a nominee.

For better or worse, Buchanan had managed, in a peculiarly perverse way, to unify many of the party’s original founders and activists, especially those loyal to the Perot faction, but his detractors lacked a serious big-name alternative to rally behind.

Real estate tycoon Donald Trump, who was pondering a possible bid for the party’s nomination, sharply criticized Buchanan’s pledge to recruit 75,000 members of his Pitchfork Brigade to take part in the Reform Party’s mail-in ballot nominating process.

“He’s got a certain group of little wacky people on the very far right,” sneered Trump — territory that the blustering, perennial presidential pretender came to know pretty well in recent years.

Jesse Ventura, the flamboyant feather-boa-wearing and libertarian-leaning governor of Minnesota who was swept into office on the Reform Party ticket a year earlier and had already removed his name from contention for the party’s presidential nomination in 2000, was reportedly giving the race a second look in light of Buchanan’s sudden entry. The outspoken ex-Navy SEAL and former professional wrestler felt strongly that Buchanan’s conservative social views would be damaging to the fledgling party.

In the weeks leading up to Buchanan’s announcement, Ventura had been actively trying to recruit either Trump or former U.S. Senator and maverick ex-Connecticut Gov. Lowell P. Weicker to enter the race, but both men eventually balked at the idea.

The 68-year-old Weicker, who had served three terms in the U.S. Senate, seriously considered seeking the party’s nomination four years earlier on a ticket with Thomas Golisano, a wealthy, self-made New York businessman. In the fall of 1999, the former independent governor had briefly flirted with the splinter American Reform Party, which enjoyed the support of former U.S. Rep. and one-time independent presidential candidate John B. Anderson and was seriously considering fielding its own candidate for the White House in 2000.

There was even some speculation in the media that Ross Perot, watching the bloodletting from the sidelines, might jump into the presidential sweepstakes for a third consecutive time.

But that turned out to be a pipe dream. Saying that the country didn’t “want to house break another president,” the party’s erratic and unpredictable founder eventually endorsed fellow Texan George W. Bush on the eve of the election, an unexpected endorsement that prompted an astonished and bewildered Buchanan to question whether there had been some “collusion” between Perot and the GOP from the outset.

Despite his considerable name recognition, Buchanan’s nomination wasn’t a foregone conclusion. In fact, a poll of Reform Party activists taken a few months before Buchanan entered the fray, showed the pugilistic conservative pundit favored by only 8 percent of the party’s membership — far behind Perot (22%), Trump (21%) and Pat Choate (17%).

In the end, no major opposition emerged and Buchanan easily sailed past little-known John Hagelin, an amiable Harvard-educated quantum physicist and three-time presidential nominee of the Natural Law Party — a party founded by a hardy band of Transcendental Meditation practitioners in 1992 — to capture the tattered party’s nomination at a raucous and bitterly-divided national convention in Long Beach, California, in August.

Hampered by a delay in receiving the party’s $12.6 million in public funding and hospitalized for gall bladder surgery shortly after the Long Beach convention, Buchanan never found his stride as a third-party aspirant for the White House.

Having made a conscious decision to focus most of his efforts in states where Republican George W. Bush was either far ahead or hopelessly behind, the Reform Party candidate appeared on the ballot in 49 states that autumn, garnering a disappointing 449,225 votes, or four-tenths of one percent, nationally.

Great article. Our country would have been much better off had Buchanan won this election.

Pingback: Trump's Non-Loyalty Oath: The Question of Independents | Hot News – News Agency

Pingback: Does Trump's Non-Loyalty Oath Strengthen His Independent Cred? - IVN.us