Trailing by more than thirty points throughout most of the campaign, New Jersey’s Barbara Buono could turn out to be the “Ertel the Turtle” of contemporary American politics, a little-known challenger who nearly caught the proverbial political hare of the day.

Viewed as little more than a sacrificial lamb from the outset, State Senator Buono might find some inspiration from the little-remembered but spirited candidacy of Democrat Allen E. Ertel who trailed by a similarly large margin throughout his long-shot gubernatorial campaign yet miraculously came within a whisker of unseating popular Republican incumbent Dick Thornburgh in neighboring Pennsylvania in 1982.

Like Gov. Chris Christie, Thornburgh was widely regarded as unbeatable that year. Moreover, there was more than a little speculation that the Pennsylvania governor, a rising star in the Republican ranks, could find his way onto the GOP’s national ticket in 1984 or 1988.

The vastly overrated Christie, of course, expects to lead that ticket in 2016. Forget New Jersey, he can’t wait to visit Iowa and New Hampshire.

As in Buono’s case, most “big name” Democrats in the Keystone State, including former Pittsburgh Mayor Pete Flaherty who had squandered an enormous lead against Thornburgh four years earlier, opted against mounting a challenge to the seemingly invincible Republican incumbent that year.

In addition to his disappointing 1978 setback, the maverick and independent-minded Flaherty — a man once mentioned by a national news magazine as a possible sleeper in the 1972 Democratic presidential sweepstakes — had also failed in two previous bids for the U.S. Senate, dropping tough races against Richard Schweiker in the Watergate year of 1974 and coming up short against Arlen Specter in 1980.

In danger of becoming Pennsylvania’s version of Harold Stassen, it was increasingly clear by early 1982 that a fourth statewide campaign in eight years didn’t hold much appeal for the former mayor of Pittsburgh and one-time Deputy U.S. Attorney General.

One by one, every conceivable major Democratic challenger bowed out of the race.

Philadelphia District Attorney Ed Rendell — the first choice of many of the state’s Democratic leaders — passed on the race. Pittsburgh Mayor Richard Caliguiri, Flaherty’s successor, quickly followed suit. State Sen. Michael O’Pake of Reading, who lost a heartbreaking contest for state attorney general in 1980, also decided not to run, as did former State Treasurer Robert E. Casey, an aging and relatively obscure Cambria County politician who listened to his bartender and parlayed the magic of the Casey name — “the real Bob Casey,” that is — to win statewide office in the year of America’s Bicentennial.

Auditor General Al Benedict, the state’s top-ranking and most powerful Democrat who later pled guilty to federal corruption, racketeering and tax charges in a job-selling scheme, also dropped out of consideration.

For months, only one Pennsylvania Democrat mustered the courage to play the role of giant slayer that year, but Jim Lloyd, a 31-year-old first-term state senator from Philadelphia — the only declared candidate in the field — eventually opted to run for lieutenant governor instead.

Nobody, it seemed, relished the idea of running against Thornburgh.

Nobody except for the little-known Ertel, who not only had a knack for seeing silver linings where others only saw dark clouds, but also enjoyed a reputation for pulling off dramatic political upsets beginning with his unexpected election as Lycoming County district attorney in the late sixties. It was a feat he repeated again in stunning fashion during a razor-thin victory over a heavily-favored Republican opponent while running for Congress in 1976.

Reelected by wider margins in 1978 and during the national GOP landslide in 1980, Ertel was the first Democrat to represent Pennsylvania’s solidly-Republican 17th congressional district in the twentieth century.

Centered smack dab in the middle of the state and encompassing five predominantly Republican counties straddling the Susquehanna River from Harrisburg to Williamsport, Ertel’s success in those races was all the more remarkable given the fact that the district’s conservative-leaning voters went for Gerald Ford by a margin of nearly 26,000 votes against Jimmy Carter in 1976 and provided Richard Nixon a whopping 71% of the vote against antiwar candidate George McGovern four years earlier.

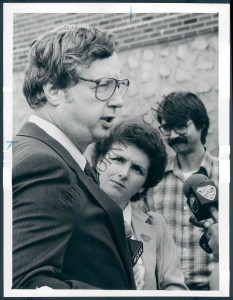

Trailing by 32 points at the outset, the little-known Ertel stormed from behind and almost unseated Pennsylvania Gov. Dick Thornburgh in 1982.

Ertel, who received an engineering degree from Dartmouth in 1958 and a master’s degree in engineering and business from the same school in 1960 before earning a law degree from Yale University after completing a stint in the U.S. Navy, had an impressive resume but was virtually unknown to most Pennsylvania voters, particularly in the heavily-populated urban centers of Pittsburgh and Philadelphia and their surrounding suburbs.

Then in his third term in the U.S. House of Representatives where he served on the Public Works and Transportation and Science and Technology committees, the cautious, 45-year-old Ertel — a man who spoke slowly, thought quickly and worked diligently — formally entered the race in late February with a low-key announcement on the steps of his boyhood home in Montoursville.

The longest of long-shot candidates, Ertel immediately took to the stump, hammering away at the state’s high jobless rate and poor economic health. Pocketbook issues — the economy — would prove to be Thornburgh’s “Achilles heel,” he asserted from the back of a green Ford pickup truck on a blustery day outside an unemployment office in the blue-collar Pittsburgh suburb of Carnegie, one of five cities that he visited a few days after officially tossing his hat in the ring.

“The Thornburgh administration really hasn’t done anything about unemployment,” he told the on-lookers, most of whom had no idea who he was or that he was running for governor. “The promise was that he was going to create jobs,” continued the little-known Ertel. “That is the cornerstone of what we’re talking about. It’s all really tied to the economy.

“We are paying more through higher taxes to support a pathetic Thornburgh administration…that is charging us more and giving us less,” he continued. According to Ertel, Pennsylvania’s unemployment rolls had swelled from 320,000 to 610,000 during Thornburgh’s tenure — resulting in a staggering jobless rate of 11.3 percent, nearly a full percentage point higher than the national average.

Despite the unanimous endorsement of the Democratic State Committee, the little-known Ertel struggled against three lesser-known candidates in the May primary. One of his opponents, a young LaRouche Democrat who promised to provide low-interest loans through the Federal Reserve to revitalize the state’s hard-pressed manufacturing, mining, construction, transportation and agricultural industries, garnered an eye-popping 143,762 votes in the Democratic primary while two other obscure hopefuls combined for nearly 177,000 votes.

Ertel had barely managed to poll 57 percent of the vote against a field of virtual unknowns.

Short on campaign cash and trailing badly in the polls, the three-term congressman from central Pennsylvania never lost hope as the autumn campaign got underway. Though troubling, the fact that his name recognition remained abysmally low late in the fall campaign wasn’t enough to discourage him.

Ertel, who carried a large green china turtle trinket emblazoned with the words “Ertel for Governor” in gold letters on his campaign travels across the state as a good luck charm, always believed that he would beat the odds.

For most of the campaign, Thornburgh ignored his Democratic opponent, pretending Ertel didn’t exist and preferring to talk about his own accomplishments. In fact, Thornburgh’s television and radio spots never recognized the challenger’s existence.

Consequently, many Pennsylvanians had no idea who was running against the popular incumbent.

With just two or three weeks remaining in the campaign, only 75 to 80 percent of the electorate could even identify the Democratic candidate. But Ertel’s handlers weren’t panicking.

“By the end of October it should be about 90 percent,” calmly explained Jon Plebani, Ertel’s campaign director.

Having raised only $700,000 as of early October — a fraction of Thornburgh’s $3.4 million war chest — former state Sen. Franklin L. Kury of Sunbury, who had selflessly volunteered to serve as Ertel’s fundraiser when the candidate had trouble enlisting a professional, literally had to beg supporters to donate an average of $100,000 a week just to keep his candidate’s modest television ads on the air during the final month of the campaign.

“I wish we had more money,” sighed Ertel.

Yet, like Barbara Buono, the long-shot candidate refused to give up. “I hope it will come together by Nov. 2,” he told a reporter during the second week of October. “The next two weeks is the magical time.”

And magical it was.

Milly Silva, Buono’s running mate for Lieutenant Governor. The duo could make history on Tuesday by becoming the first all-female ticket elected in history.

Considered a “sacrificial lamb” until late September when the national economic recession hit Pennsylvania with full force, Ertel campaigned vigorously from sun up to past midnight seven days a week, blaming “Reaganomics” — and Thornburgh’s support of President Reagan’s economic and fiscal policies — for the state’s high unemployment rate and sluggish economy.

He also succeeded in convincing a large number of voters that Thornburgh was responsible for their higher property taxes and rising utility rates while painting the incumbent Republican as callous and mean-spirited toward the state’s most vulnerable citizens.

Thornburgh, who adamantly refused to debate his Democratic opponent, countered by sharply criticizing Ertel’s forward-looking economic program which included the creation of an autonomous Capital Development Corporation — an idea originally championed by his running mate, Jim Lloyd — to provide low-cost loans to Pennsylvania manufacturers for the modernization of machinery and equipment. According to Ertel, the corporation would finance the loans by tapping into some $8 billion in public employee pension reserves.

The low-key Democratic candidate also advocated the establishment of an Economic Development Board, consisting of five members from industry, five from labor and five from state government, with the governor serving as the presiding officer, to develop economic policy and goals.

As mentioned, Thornburgh quickly denounced Ertel’s sweeping economic proposals, accusing his Democratic rival of practicing “snake oil” politics by proposing to invest pension funds in what he described as “high-risk” loans.

Thornburgh’s criticism drew a quick response.

“If he’s attacking my programs,” Ertel retorted, “he’ll have to start explaining why he doesn’t have any. He can’t just say he’s cleaned up government and gotten the budget through on time. He’ll have to explain why Pennsylvania has more layoffs than any other state and he can’t do anything about it.”

Bolstered by his own internal polling that showed him within 4 percentage points, or the margin of error, the little-known congressman beamed with optimism in the campaign’s final hours. The possibility of a dramatic come-from-behind victory wasn’t as far-fetched as it once seemed.

Ertel’s pollster agreed. “The direction is positive,” said Mike Young of the Cromer-Young Group of Harrisburg. “He has momentum which appears to be accelerating. There’s a general Democratic trend. If the trend continues, it’s going to be a horse race come Monday or Tuesday.”

Frantically crisscrossing the state on the eve of the election, “Ertel the Turtle” — a candidate given up for dead before the campaign even started — believed he was on the verge of pulling off a major upset. “I think we’re catching up,” he told supporters.

“I think we’re going to see a new dawn in Pennsylvania politics starting Wednesday,” he added. “If we get out the vote, we’ll win this election.”

Ira Cooperman, Ertel’s press secretary, concurred. “A lot of people out there are sniffing victory,” he said elatedly.

Despite the daunting poll numbers — some surveys continued to show Thornburgh leading by as many as twenty points as Pennsylvanians trekked to the polls on Nov. 2nd — Ertel came within an eyelash of springing one of the most startling upsets in modern American political history.

The race was much closer than anybody expected. Thornburgh, who began the campaign with a 32-point lead in the polls, barely survived Ertel’s surprising last-minute surge — a rally from the grave in the campaign’s final hours.

The contest was so close that CBS, which had conducted exit polls throughout the day, delayed its projection for several hours and at one point NBC, which had already declared Thornburgh the winner, withdrew its earlier projection and said the race was too close to call.

Thornburgh had jumped out to an early lead as the returns began trickling in that evening, but within a few unforgettable hours Ertel had whittled the lead down to a mere 7,000 votes. Incredibly, for more than an hour the two men were running neck-and-neck, at roughly fifty percent apiece, before Thornburgh slowly began to pull away late.

Remarkably, the little-known congressman held Thornburgh’s margin in the state’s traditionally Republican “T” — the areas outside the Democratic strongholds in southeastern and southwestern Pennsylvania — to a breathtakingly narrow 109,000 while carrying ten counties in the region and falling only a few hundred votes short in several others.

Through sheer tenacity, Ertel managed to turn many of the state’s Republican-leaning counties in the region into unlikely battleground spots.

Needless to say, Thornburgh, who had expected a much easier victory, was absolutely stunned. For hours, he remained secluded in his hotel room with his wife, Ginny. It wasn’t until nearly midnight — some four hours after the polls had closed — that his pesky, underfunded Democratic rival finally conceded.

When all the votes were counted, Thornburgh narrowly escaped a career-ending defeat, garnering 1,872,784 votes to Ertel’s 1,772,353. He won by just 2.7 percent.

“I have often used the term ‘swimming against the tide,’” the visibly shaken governor told his obviously relieved supporters at the Franklin Plaza Hotel in Philadelphia, “but I tell you I didn’t know how tough a swim and how rough a tide that could be until tonight.” Noting that infuriated voters, concerned primarily with pocketbook issues, had rejected several of his Republican colleagues across the country that night, Thornburgh said later that he was “darn glad to be among the survivors.”

An exhausted Ertel accepted his defeat graciously. “Although we didn’t win the election,” he told his disappointed supporters in Williamsport, “we won the campaign. We leave the campaign with our pride and dignity intact.”

As in Tuesday’s contest in the Garden State, everybody had written off the governor’s race in Pennsylvania that year, saying it would be a landslide — yet Ertel somehow managed to surprise everybody.

While few believed that the relatively obscure Ertel could make a race of it more than three decades ago, even fewer believe that Barbara Buono poses much of a threat to the blunt-talking, media-adored Christie on Tuesday. Yet there are many striking similarities between the two long-shot candidacies.

Both were initially regarded as sacrificial lambs and consistently trailed by large margins throughout their respective campaigns — often by more than thirty points.

Both campaigned doggedly against incumbents with sky-high approval ratings and unfulfilled national ambitions.

Both had young and dynamic running mates; the late Jim Lloyd —a young, talented politician who never forgot a name or a face — ran with Ertel while Milly Silva, New Jersey executive vice president for 1199 SEIU, a local health care workers union affiliated with the Service Employees International Union, has been paired with Buono. It’s only the third all-female major-party gubernatorial ticket in American history. If the voters are so inclined, New Jersey could be the first state in the country to elect such a combination.

Both candidates — Ertel and Buono — also hailed from deeply blue states; the Democrats enjoyed a 750,000-voter registration edge in Pennsylvania in 1982, while Buono’s party currently holds a 733,000-voter registration advantage in neighboring New Jersey.

Both were vastly outspent; Ertel by more than three-to-one and Buono by an even more lopsided margin (as of October 31, Gov. Christie had raised $13.2 million to his Democratic challenger’s relatively meager $2.8 million).

Both contenders, interestingly enough, dramatically cut into their opponents’ overwhelming leads late in the campaign. Ertel, who was never given a chance to unseat the immensely popular Thornburgh, trimmed a staggering 32-point deficit down to 13 points with two weeks remaining in 1982 while Buono, coming from an even more distant 33 points behind, has recently pulled within 19 points — 59 percent to 40 percent — according to a Fairleigh Dickinson University poll released Friday.

And both underdogs campaigned during periods of economic uncertainty; Ertel during the Reagan recession of 1982-83, and Buono at a time when New Jersey suffers from a jobless rate of 8.5 percent — significantly higher than the national average and the eighth worst in the country — massive “underemployment” (nearly one out of every six New Jersey residents currently falls into that category) and the second-highest foreclosure inventory in the nation.

That’s just the tip of the iceberg. Under Christie’s watch, job creation in the private sector has come to a screeching halt, the state’s credit rating has plummeted to the third-lowest in the country and property taxes — always a hot-button issue in a state with the steepest property taxes in the nation — have climbed 8.3 percent while government services have been curtailed.

Look out, New Jersey. Things are likely to get worse before they get better, especially if Gov. Christie becomes a full-fledged austerity ghoul hoping to impress his party’s feverishly right-wing base in 2016.

If recession-ravaged New Jerseyans were really honest about it, they would have to concede that Christie’s first four years in office have left the state lagging behind virtually every other state in the region.

Hype and celebrity doesn’t bring prosperity. The state can do much better.

Coupled with jaw-dropping corporate giveaways totaling in the billions, growing income inequality and a disturbingly dramatic rise in child poverty, Christie’s record in New Jersey — a dismal record that remains largely unexamined by a mainstream media smitten with the biggest bag of bluster in American politics — could make him vulnerable to an unexpected last-minute surge by a spunky Democratic challenger (a proverbial tortoise, you might say) ready to pull off the biggest political upset in recent U.S. history.

A closer-than-expected race on Tuesday would be great for American politics. An upset of gargantuan proportions would be even better.

Follow Us