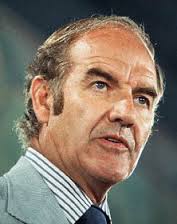

Trailing by a staggering 34 points in the polls, Democratic presidential candidate George S. McGovern of South Dakota accused the Nixon White House of ordering a “whitewash” in a federal grand jury investigation of the Watergate break-in on this day in 1972.

Trailing by a staggering 34 points in the polls, Democratic presidential candidate George S. McGovern of South Dakota accused the Nixon White House of ordering a “whitewash” in a federal grand jury investigation of the Watergate break-in on this day in 1972.

“From the first count to the last, the federal grand jury indictment returned yesterday in the Democratic bugging case spells whitewash,” McGovern told reporters while standing on the front porch of his Japanese-style home in a fashionable section of northwest Washington, D.C.

“And I suggest,” continued McGovern, who had just returned from an exhausting 11-day campaign swing, “that this blatant miscarriage of justice was ordered by the White House to spare them embarrassment in an election year.” The alleged cover up, he insisted, was part of a disturbing and “growing pattern of immorality” on the part of the Nixon administration.

It was, until then, one of McGovern’s strongest condemnations of the Nixon presidency — and it was splashed on the front pages of newspapers across the country and carried on the network television newscasts that weekend.

Leaving little doubt that he intended to make the Watergate burglary a major issue in the remaining six weeks of the campaign, McGovern’s hastily-called Saturday news conference came in response to the previous day’s grand jury indictment of two former White House aides and five burglars arrested by police at the Watergate headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in the early morning hours of June 17th.

The two indicted White House aides were the notorious G. Gordon Liddy, a former presidential assistant for domestic affairs who was serving as counsel to the Committee for the Re-election of the President (CREEP) at the time of the Watergate break-in, and his close associate E. Howard Hunt, Jr., a former White House consultant and longtime CIA operative.

Renewing his call for an “impartial” investigator — possibly ex-Chief Justice Earl Warren or former solicitor general J. Lee Rankin — McGovern declared that it Nixon failed to appoint such an investigator, it would be “a very serious dereliction of duty.”

Responding to the Democratic nominee’s allegations, Henry E. Petersen, assistant attorney general for the Justice Department’s Criminal Division, said that McGovern’s charges were “completely unfounded” and were “a grievous attack on the integrity of the 23 good citizens of the District of Columbia who served on the Watergate grand jury faithfully and well.”

The investigation, said Petersen, had been “the most exhaustive and far-reaching” in his 25 years in the Justice Department. He also maintained that there had been no effort on the part of the White House to interfere with the investigation.

McGovern continued to rail against the break-in and bugging of the Democrats’ Watergate headquarters “by the five burglars with their rubber gloves in the dead of night” for the remainder of his long-shot campaign.

So, too, did R. Sargent Shriver, McGovern’s vice-presidential running mate. Second only to the American Independent Party’s witty John G. Schmitz, who delighted in delivering some of the funniest one-liners that autumn, Shriver had a marvelous sense of timing and delivery when it came to humor — much of it furnished by Ohioan Robert Hagan, a politician and joke writer who had previously written material for comedian Danny Thomas.

Like McGovern, Shriver tried valiantly to make the Watergate break-in a major issue in the closing weeks of the 1972 campaign.

The former Peace Corps director, whose own law office in the Watergate also happened to be bugged by Nixon’s “plumbers” that spring, repeatedly reminded audiences throughout the country of the Watergate break-in, explaining how the sleazy burglars with “money in their pockets” directly traced to the President’s re-election campaign had been caught red-handed, yet “the White House was as silent as the grave where Checkers lies buried” — a reference to Nixon’s famous 1952 speech invoking the name of his children’s dog.

“This is not a secret trip,” Shriver said during a campaign tour. “Only the Republicans make secret trips; one to Russia, one to Peking, and at least one to our Democratic headquarters.”

Unfortunately, precious few paid any attention.

Incredibly, a Gallup poll released in October, shortly before the election, reported that only half of the American people had heard of the Watergate break-in and, according to another pollster, only six percent of those surveyed believed that Nixon was personally involved.

Shriver shrugged at this otherwise startling revelation, saying that the American people were apparently “too bruised” to care any more when it came to public corruption. “We’ve lost our sense of moral outrage,” he said wistfully.

On Election Day, McGovern carried only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia while losing to Nixon in a landslide. Nixon captured nearly 61 percent of the popular vote. It was one of the worst drubbings in presidential history.

Of course, the public mood shifted dramatically as the Watergate scandal continued to unfold.

By August 1973 — only nine months after the election — Gallup reported that Nixon’s approval rating had fallen to an all-time low, and an NBC News poll conducted by Oliver Quayle & Co. showed that McGovern would now defeat Nixon by a margin of 51-49 percent.

Despite suffering one of the most painful electoral defeats in history, McGovern later felt totally vindicated by his role in the 1972 presidential campaign. “There are worse things than losing,” he reflected more than a decade later while addressing students at Northwestern University. “That landslide, victorious team of ‘72 spent a total of 180 years in prison, and the President resigned in disgrace.”

Follow Us