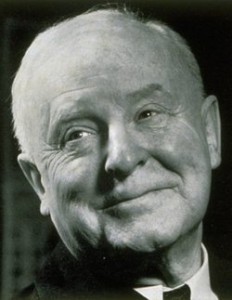

Twenty years before his death on this day in 1944, legendary newspaper editor William Allen White, a man who advised Presidents and rubbed shoulders with some of the world’s greatest statesmen in a career that spanned five decades, waged one of the most fascinating and extraordinary political campaigns in the country, nearly toppling his major-party rivals in a bid to become governor of Kansas.

Twenty years before his death on this day in 1944, legendary newspaper editor William Allen White, a man who advised Presidents and rubbed shoulders with some of the world’s greatest statesmen in a career that spanned five decades, waged one of the most fascinating and extraordinary political campaigns in the country, nearly toppling his major-party rivals in a bid to become governor of Kansas.

While most of the country was riveted on the three-way presidential contest between President Calvin Coolidge, Democrat John W. Davis and the insurgent “Fighting Bob” La Follette of Wisconsin that autumn, the widely-known “Sage of Emporia” was kicking up the dust in America’s heartland.

Running as an independent, the 56-year-old White drew incredibly large crowds as he traveled from one corner of the state to the next in a dilapidated automobile, spending his meager campaign funds on gas and oil for his old clunker, as well as an occasional hotel room. Rarely was he lucky enough to be accompanied by a volunteer band to entertain his crowds — a standard campaign practice in those days.

Lacking a campaign war chest, the fiery small-town editor withdrew $25 from his bank account every Monday morning to pay for his weekly campaign expenses. Without a campaign manager and virtually no organization, headquarters or campaign literature, White collected more than 10,000 signatures on his nominating petitions — until then “the largest independent petition ever filed for any office in Kansas” and more than four times the minimum required. Moreover, the lifelong Republican refused to circulate petitions in his hometown or county, reasoning that if he wasn’t “well enough known in other parts of the state to get 10,000 signatures,” then he really shouldn’t be running.

White’s entry into the race as an independent stunned the GOP hierarchy in Kansas and nationally. Except for a brief lapse in 1912 when he actively snorted and thundered in support of Teddy Roosevelt’s Bull Moose candidacy — “Roosevelt bit me and I went mad,” he joked years later — White was one of the best known and most loyal Republicans in the state.

Initially bursting onto the national scene with his famous “What’s the Matter With Kansas?” editorial — a scathing attack on Populism that was quoted time and again in many of the nation’s leading publications — White was not a politically ambitious person and was running solely because the nominees of the two major parties had not sufficiently repudiated the Ku Klux Klan in their respective primaries. In fact, Gov. Jonathan M. Davis, the Democratic nominee, and Republican challenger Ben S. Paulen both accepted Klan support in winning their parties’ nominations.

Any candidate who lacked the courage or the righteous indignation “to denounce and defy the Ku Klux Klan in the primary and in the election,” declared White, “is not going to oppose it seriously in the governor’s chair.”

“I want to be governor to free Kansas from the disgrace of the Ku Klux Klan,” asserted the crusty, Pulitzer-prize winning editor in announcing his candidacy in September. “And I want to offer Kansans afraid of the Klan and ashamed of that disgrace a candidate who shares their fear and shame. I am in the race to stay, and to win.”

With a single-minded and almost fanatical zeal, White barnstormed the Kansas prairies, focusing almost all of his energy and vitriol against the hooded order, which enjoyed a rebirth not only in Kansas, but across the country shortly after World War I. By the early 1920s, membership in the Klan swelled to more than four million nationally.

“The issue in Kansas is the Ku Klux Klan above everything,” said White. The Klan, he asserted, was organized solely for the purpose of terrorizing African-Americans, Jews and Catholics — groups that made up nearly a quarter of the state’s population in 1924. He was appalled that his major-party opponents were unwilling to defend the groups targeted by the Klan.

“They are good citizens, law abiding, God fearing, prosperous, patriotic, yet because of their skin, or their race, or their creed, the Ku Klux Klan in Kansas is subjecting them to economic boycott, to social ostracism, to every form of harassment, annoyance, and every terror that a bigoted minority can use,” declared White, who promised restore his state to a time in the not-so-distant past when Kansans “didn’t take a microscope and examine a man’s skin, look at his birth certificate and give him a theological examination before determining whether he should be an American citizen.”

The Klan, he said, was a national menace that “knows only bigotry, malice and terror.”

Although campaigning was something of a new experience for him — he famously turned down the Progressive Party’s offer to be its gubernatorial nominee in 1914 — the revered country editor admitted that he was having the time of his life and seemed to particularly relish the opportunity to criticize both major parties, something he hadn’t done in more than a decade.

“The two major parties in Kansas,” he told voters, “are the toys and playthings of the willipus-wallipuses of Georgia, also the wizards of one sort and another of Wall Street, who are trying to run the country.”

White’s candidacy drew national and international attention. The New York Times and one of the largest dailies in London sent reporters to Kansas to cover his remarkable six-week campaign. The national media generally applauded White’s courage and independence in taking on the Klan, but many native Kansans felt that his candidacy was attracting unwarranted negative attention to their state by focusing on the Klan, which many believed was already on the decline.

White and his running mate for lieutenant governor, Carr W. Taylor — a state Senator from Hutchinson who shared White’s disdain for the Klan — scared the daylights out of their Democratic and Republicans rivals that fall.

Though he didn’t formally declare his candidacy until September 20 — only six weeks before the election — White traveled nearly 2,800 miles in his 1919 Dodge automobile while giving more than one hundred speeches throughout the state. Incredibly, he spent only $474.60 on his entire campaign, most of it on bare essentials like gasoline and lodging.

Despite his valiant effort, the progressive pundit fell short on Election Day, garnering an impressive 149,811 votes, or 22.7 percent, to Paulen’s 323,402 and 182,861 for the incumbent Davis.

Excerpts from Darcy G. Richardson’s OTHERS: “Fighting Bob” La Follette and the Progressive Movement, published in 2008.

Pingback: Skull / Bones » Blog Archive » links