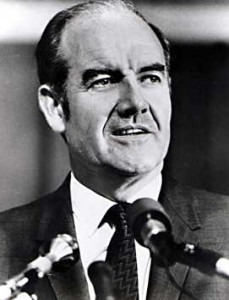

Following closely on the heels of a decisive win in Pennsylvania a week earlier, Sen. Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota was catapulted into serious contention for the Democratic presidential nomination by scoring a pair of victories in Indiana and Ohio on this day in 1972.

Following closely on the heels of a decisive win in Pennsylvania a week earlier, Sen. Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota was catapulted into serious contention for the Democratic presidential nomination by scoring a pair of victories in Indiana and Ohio on this day in 1972.

Given up for dead in the wake of his loss to Richard M. Nixon in 1968, a lack of campaign cash is probably the only thing that prevented Humphrey — one of the last Democratic presidential nominees molded in the tradition of FDR — from staging one of the most remarkable political feats in the annals of American politics.

While he had his faults, Humphrey was a Democrat’s Democrat. Unlike the current Wall Street-occupied White House, one couldn’t possibly imagine a Humphrey Administration conceiving of the idea of a sequester or seriously contemplating — even for a nanosecond — the idea of giving the maniacally mean-spirited, Tea Party-fueled austerity peddlers in Congress precisely what they want by agreeing to put Social Security and Medicare on the table.

Following his narrow defeat in 1968, the former Vice President returned to Minnesota and accepted teaching jobs at Macalester College and the University of Minnesota, his alma mater. He also found time to write a syndicated column and earned dozens of $2,500 speaking fees on the lecture circuit.

In addition, Humphrey served as a roving ambassador and member of the board of directors for Encyclopedia Britannica at a salary of $75,000 a year and received a $70,000 advance to write his memoirs. Coupled with a $19,500 federal pension, Humphrey earned more than $200,000 in 1969 — more money than at any time in his life. Always a loyal party man, he also spent a considerable amount of time as a featured speaker at DFL fund-raising events in Minnesota.

“All such rewards at this point were no more than ashes in Humphrey’s mouth,” wrote biographer Carl Solberg. He missed public life and the thrill of politics. After briefly flirting with the idea of running for governor of Minnesota, Humphrey eventually ran for the U.S. Senate seat vacated by Eugene McCarthy in 1970.

Sporting an entirely new image, the 59-year-old Humphrey barely resembled the desperate man who frantically tried to come-from-behind against Nixon two years earlier.

Dressed in sharp William Fioravanti-tailored suits, Humphrey, who shed a dozen pounds and darkened his thinning hair a deeper black, looked like a new man. He also had a new slogan — “You Know He Cares.” Easily winning the DFL primary, Humphrey trounced Republican Clark MacGregor, a five-term congressman, in the general election.

Returning to the Senate, Humphrey made it clear that he had not changed. “I’ve never been known as ‘Hubert the Silent,’” he laughed. “I don’t intend to get a new reputation at this stage in life.”

Unlike Barry Goldwater, who retained his seniority and was given his old committee assignments when he returned to the Senate in 1969 following a four-year hiatus, Humphrey was greeted with something less than open arms when he returned to the Senate in January 1971.

In truth, his former Democratic colleagues treated him rather shabbily.

Despite sixteen years of experience in the U.S. Senate, Humphrey soon found himself ninety-third out of a hundred in the pecking order of seniority and — adding insult to injury — was denied his former seats on the Appropriations and Senate Foreign Relations committees and had to settle for the far less glamorous Government Operations and Agriculture committees. He also ended up on the Joint Economic Committee, mostly because nobody else wanted the assignment.

Humphrey felt the Senate had changed and confided in his old friend Eugenie Anderson, a former U.S. ambassador to Denmark and Bulgaria, that it was “anything but an exhilarating and inspiring experience.” Gone was the camaraderie and intimacy he enjoyed as Majority Whip from 1961-1964. Gone, too, were many of the men he served with earlier, such as Georgia’s Richard Russell, the dean of the Senate, who passed away just as Humphrey was being sworn in on January 21, 1971.

Humphrey nevertheless threw himself into his work, busying himself with constituent services and introducing countless pieces of legislation, including a billion-dollar bill to eradicate cancer and a revenue-sharing measure in which the federal government would have borne all the costs of the nation’s welfare programs. He also proposed legislation to create a National Domestic Development Bank — a bold idea that we could sorely use today — to provide capital and technical assistance to financially hard-pressed local governments.

Hoping to put the issue of the war behind him once and for all, the “Happy Warrior” also endorsed the dovish Hatfield-McGovern amendment calling for a scheduled withdrawal of all U.S. troops from Vietnam by the end of 1971.

“It maybe isn’t the best of all things,” he told a reporter at the time, “but I think that whatever reason we had to be there — and only history is going to judge whether that reason was right or wrong…but whatever the reasons, we have more than fulfilled it…I submit that national pride is meaningless if your country is torn apart.”

No longer trapped in Johnson’s shadow — a dark adumbration that most likely cost him the presidency in 1968 — Humphrey had come full circle on the war in southeast Asia.

He had also come to believe that America’s youth — many of whom had been galvanized by Gene McCarthy’s antiwar candidacy — were perhaps the most promising thing that had come out of the experience of 1968. The kids, he said, had blown “the whistle on our use of power as the main instrument in our international affairs.” They questioned our values and the nation’s role in the world, “and now it’s seared into our flesh.”

During his 1970 Senate campaign, Humphrey said there was little chance he would ever again be his party’s nominee for the nation’s highest office. “I can’t imagine getting the nomination in ’72,” he said wistfully.

Yet he believed Nixon could have trouble winning a second term. “I think Nixon is a one-term president,” he told reporters shortly after winning his Senate race. “I realize it is difficult to unseat an incumbent president, but he is vulnerable. In fact, I believe the only thing that will beat us [the Democrats] in 1972 will be our own mistakes.”

By the spring of 1971, it was clear that Humphrey was itching to run again. “I’ve got the sails up. I’m testing the waters,” he told reporters at a National Press Club breakfast on May 27. “I’m not salivating,” he added, “but I’m occasionally licking my chops.”

A Gallup Poll released in late December 1971 unexpectedly showed Humphrey with a five-point lead over Sen. Ed Muskie of Maine, who had long been regarded as the frontrunner in the race for the party’s nomination. That was all the encouragement he needed.

There’s no cure for Potomac fever.

Shrugging off critics who viewed him as a Democratic version of Harold Stassen, Humphrey decided to take the plunge, announcing his candidacy at the Poor Richard Club in Philadelphia — the nation’s birthplace and a favorite hangout for the city’s more affluent Democrats — on January 10, 1972.

“Persistence and tenacity are old American virtues,” he said, reminding skeptics that he had lost time and again in the past, but always managed to come back and win the second time.

Declaring that it was “taking Mr. Nixon longer to withdraw our troops than it took us to defeat Hitler,” the thrice-defeated presidential hopeful waged a vigorous campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination, routinely logging eighteen-hour days.

“This is it for me. It’s now or never,” he declared while campaigning in Florida‘s crowded primary. “I’ve gotta go, go, go.”

True to his word, the ebullient 61-year-old former Vice President waged a campaign so vigorous that it left his aides and the reporters traveling with his campaign almost literally gasping for air. Humphrey’s energy knew no bounds, prompting his physician and longtime political confidant, Edgar Berman, to joke that his seemingly endless stamina was “a serious genetic defect.”

While most of the other contenders in the crowded Democratic field were sloshing through the snows of New Hampshire, Humphrey made an all-out effort in Florida’s March 14 primary. Despite an enormous personal effort — he spent far more time there than any other candidate, at one point spending 20 of 26 days there — and spending more than $1.5 million, Humphrey finished a distant second to Alabama’s George C. Wallace in that contest, netting only six of the state’s 81 delegates.

After finishing 100,000 votes behind George S. McGovern and 15,000 votes behind Wallace in the Wisconsin primary three weeks later, the indefatigable Humphrey quickly bounced back, running off a string of three straight primary victories, beginning with the Pennsylvania primary on April 25 and followed by narrow wins over McGovern in Ohio and Wallace in Indiana on May 2.

Humphrey’s margin of victory over McGovern in Ohio was a razor-thin 19,340 votes, or less than two percent of the total. He enjoyed a somewhat more comfortable margin against Wallace, spanking the Alabama governor by 45,000 votes, or by nearly six percent, in the Hoosier State.

The double-barreled victory breathed new life into his candidacy.

His winning streak, however, came to an abrupt end only a week later, on May 9, when he was beaten by McGovern’s much better organized campaign in Nebraska — losing a hard-fought contest to the South Dakotan by a margin of 79,309 votes to 65,968. The Minnesotan, however, salvaged some of his momentum by rolling up an impressive 67% of the vote against Wallace — still very much a symbol of white supremacy in ’72 — in a one-on-one showdown in West Virginia the same day.

Following disappointing losses in the May 16 Maryland and Michigan primaries, Humphrey’s campaign was flat broke and his advisors decided he would have to forego New York’s delegate-rich primary on June 20, where 278 delegates were at stake. “I was furious,” Humphrey said later, “but they told me they didn’t have the money.” As it was, Humphrey’s campaign was already more than a million dollars in debt — big money back then.

McGovern snapped Humphrey’s winning streak, slowing his momentum, with a victory in the May 9th Nebraska primary.

Then came the pivotal California primary, one of only four states with a winner-take-all primary in the great reform year of 1972. It was the biggest prize of all.

Virtually ignoring Oregon, New Jersey and New York during the final month of the campaign, Humphrey risked all of his chips on a seemingly unlikely come-from-behind victory in California, gambling everything on a stunningly seismic upset that would’ve catapulted him into the lead heading into that summer’s Democratic convention.

Such a scenario was probably Nixon’s worst nightmare.

Believe it or not, Humphrey — though nearly penniless — was still within striking distance of winning the nomination. Heading into the campaign’s final month, Newsweek magazine projected McGovern’s delegate count at 900 to Humphrey’s 760, with 1,509 needed to win the nomination.

For all intents and purposes, California’s 271 delegates were the whole ballgame for the former Vice President, but he desperately needed money in order to compete there.

Having already tapped out his wealthier supporters, Humphrey turned in desperation to the unions, but they too had little or nothing more to give.

It’s the Super Bowl of Democratic politics, Humphrey pleaded with I. W. Abel of the powerful Steelworkers union. “If we win, we go on to win in Miami. If we lose, that will be like falling in a ditch with a bulldozer filling it in.”

As in Wisconsin — where he spent only $89,500 — Humphrey was again forced to wage a frugal, low-budget campaign. He couldn’t afford any television and even something as inexpensive and basic as producing cheap, black-and-white fliers proved to be an economic hardship in the California primary.

In the meantime, campaign treasurer Eugene Wyman, a Beverly Hills lawyer and old Humphrey friend who managed to squirrel away some $400,000 for the critical June 6 primary, was forced to send most of that money to Washington shortly before the primary to keep the candidate’s national headquarters from being padlocked. Moreover, several checks written by Humphrey’s national office had to be covered without delay. “Those checks, coming to approximately three hundred thousand dollars, had to be covered immediately or they would bounce,” Humphrey later recalled.

Needless to say, Humphrey’s plans for an intensive media campaign in California went up in smoke when Wyman, following his candidate’s directive, sent off $250,000 to bail out the candidate’s debt-ridden national office. Humphrey now had little money in which to compete with McGovern’s comparatively hefty two million dollar California war chest.

With McGovern leading by double-digits in the polls, it appeared as though the race was over. “It won’t be a convention, but a coronation,” crowed McGovern campaign manager Frank Mankiewicz.

Having exhausted his support from organized labor and lacking the resources to purchase badly-needed television advertising, Humphrey — trailing McGovern by a seemingly insurmountable twenty points in the respected California Field Poll — had to rely almost exclusively on free airtime, including three face-to-face televised debates with McGovern in which he savagely tore into his rival on everything from defense to welfare.

Refusing to abandon his lifelong dream of occupying the White House, Humphrey turned increasingly negative — and uncharacteristically mean-spirited — toward his Democratic colleague from South Dakota. Among other things, he harshly criticized McGovern’s ill-conceived welfare proposal to provide a one-thousand-dollar income supplement to everyone in the country, charging that the “preposterous” scheme would cost the U.S. Treasury $72 billion.

“I’ll be damned if I’m giving everybody in the country a thousand-dollar bill,” shouted Humphrey, who was clearly fighting for his political life. “People in this country want jobs, not handouts.”

McGovern was flabbergasted, never expecting to be hammered so ruthlessly by somebody he had long considered a close friend.

Humphrey’s relentless attacks on his old friend and neighbor worked as McGovern’s huge lead in the polls began to rapidly evaporate. Unfortunately, Humphrey’s aggressive assaults on McGovern’s defense, tax and welfare proposals would come back to haunt the Democrats in the fall when the Nixon campaign gleefully exploited those very issues.

The contest in California turned out to be much closer than anybody anticipated, and it wasn’t until three o’clock in the morning of June 7 that the major television networks finally proclaimed McGovern the winner. The fatigued and battle-worn Humphrey lost by fewer than five points, losing to McGovern by a margin of 43.5 percent to 38.6 percent.

Humphrey believed that he might have won the California primary and its 271 delegates if he had been able to raise another $150,000 for paid television — chump change in today’s ridiculously expensive and consultant-driven, post-Citizens United world.

Proving that dreams die hard, Humphrey briefly — yet somewhat shamefully — aligned himself with the last-ditch “Anybody but McGovern” movement before eventually withdrawing from the race during the Democratic national convention in Miami Beach, thereby ending his lifelong quest for the brass ring.

Excerpts from Darcy G. Richardson’s A Nation Divided: The 1968 Presidential Campaign, published in 2002.

Pingback: YORKTOWN TRADING POST » Time Capsule: Pair of Primary Wins Propel Humphrey into Serious Contention in … – Uncovered Politics

Declaring that it was “taking Mr. Nixon longer to withdraw our troops than it took us to defeat Hitler” …

One might consider that, in the Vietnam “conflict” the U.S. had a formidable foe backing the North Vietnamese, so Nixon’s delay withdrawing U.S. troops might be regarded understandable. However, when one considers that, today’s enemy in the U.S.’s so-called war on terror possesses neither an industrial base feeding materiel needed to successfully prosecute war, nor a first rate intelligence service needed to win war, the idea of an “enemy” whose illusive defeat is extending this war’s prosecution far in excess time we spent in Vietnam fighting a Soviet-backed enemy, and far, far exceeds time spent defeating Hitler’s Nazis, well, the contrast here rather decidedly suggests to anyone capable of thinking in this nation that spends more on its defense and intelligence than all other nations on the planet combined, that the enemy in fact is within.

Forgive me for stating the obvious…